Author: Renee Schiavone | Published: July 7, 2023 | Category: Look Back

The recap and realizations of two ONDA board members rafting 55 miles of the Owyhee River.

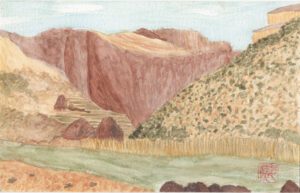

Close your eyes and imagine a place so grand it makes you feel small compared to the size of the thick, rocky walls that surround you. You can almost feel everything that happened before you to form this amazing landscape, making you acutely aware of not just how small you are in this moment, but in your universe. Inside these walls that encapsulate you, you’re floating. Down a river, through a canyon, all of your senses are heightened. Your ears perk to the sound of rushing water ahead, your eyes dart open to follow the dancing of an ouzel on the river bank.

It’s impossible to truly imagine what a week floating down the Owyhee River is like, but with the help of ONDA board member Elisa Cheng and board vice president Natasha Bellis, we can try. The two recently spent 6 days rafting 55 miles of the Lower Owyhee River from Rome to Birch Creek with Ouzel Outfitters. Prior to the trip, neither had any previous experiences in or connections to the Owyhee Canyonlands. Not for lack of interest, but rather approachability.

“The Owyhee was rarely on my way to anywhere,” said Natasha, and “I just didn’t take the time to get out there before this trip,” added Elisa, “as the drive was pretty long.” It’s true; located in the far southeast corner of the state, Oregon’s Owyhee Canyonlands are one of the most wild places in the entire country – and that’s part of the appeal. “Ever since I heard of the Owyhee Canyonlands 20 years ago,” said Natasha, “I envisioned this mysterious, almost mystical, landscape that was part Grand Canyon and part high desert. Floating through the landscape was high on my list, but I needed the right opportunity to present itself before I could finally do it.”

Geology and History of the Owyhee

The geology of the Owyhee Canyonlands is quite diverse and breathtaking, ranging from millions of years ago when the land was part of the supervolcano that’s now Yellowstone. In addition to the honeycomb-like spires and vast rhyolite domes, one of the most immediate and impressive features are the deep canyons cutting through the area. Much of the rock in these canyons was produced by huge caldera-forming eruptions, associated with the Yellowstone Hotspot. These very explosive eruptions left behind thick deposits of rhyolite ash and pumice, some of which are hundreds of feet thick, so when the river cut through them it created the vertical walls we see in the Owyhee Canyonlands today.

Floating down the Owyhee River is when it’s most apparent the canyon has taken many courses throughout its life. “From busting through and rerouting around lava dams to depositing amazing silts and sediments that eroded over time, it’s created features that look like castles and spires layered with amazing colors,” says Natasha.

While the profound landscape speaks for itself, the deep history displays itself in subtle ways. Home to a living cultural richness for the Indigenous Northern Paiute, Bannock and Shoshone tribes, these ancestral lands contain areas considered sacred. Going back at least 13,000 years, semi-nomadic hunters and gatherers inhabited the vast canyons and sagebrush of the Owyhee. The evidence of tens of thousands of years of habitation can be seen in the more than 500 known archaeological sites in Oregon’s Owyhee Canyonlands alone. In addition to preserved boulders carved with petroglyphs, landscapes, rivers, fish and wildlife here support tribal traditions and practices to this day.

After just day one, Natasha noted she was, “blown away by the remoteness, the beauty and the history. It far exceeded my expectations. I didn’t expect to learn so much about the geology of the Canyonlands and see so much evidence of indigenous cultures. Days seemed to slip by in a matter of minutes as we floated speechless between the walls of jaw-droppingly beautiful thousand-foot cliffs, plummeted through heart-racing rapids and contemplated early human existence on this landscape as we wandered through fields of petroglyphs.”

Rafting the Canyon

Rafting the lower Owyhee River is highly regarded as a once-in-a-lifetime experience that introduces you to some of the most spectacular and untouched high desert landscapes found in eastern Oregon. Deep canyon walls, riverside camps, and hikes climbing to sweeping vistas are all highlights of this trip. Spanning three states, the vast Owyhee watershed includes over 500 miles of rivers and streams.

Witnessing the smiles on Elisa and Natasha’s faces firsthand, you can tell the experience was truly incredible. River guides describe the Owyhee River as “spicy”. From a first-timers perspective, Elisa would agree with that assessment. “You never knew what was going to be around the next corner. Little trains of waves would push you forward as you floated along cooling you down from the brilliance of the sun. All of the golds and browns of the desert reflecting off the water were mesmerizing.”

With so many memorable moments, it’s hard to recall just one. For Elisa, one that will undoubtedly live with her forever was “walking along the river just before dinner one evening. The sun was getting low in the sky and the golden hues infused every part of the landscape. The water looked like it was gilded. The picture I took really just does not do it justice. But that was my favorite moment. I only took one picture because I decided I didn’t want to miss the sun setting for a minute and wanted to just walk along and enjoy it.”

Connection to the Desert

Spending an extended amount of time in the high desert will foster a deeper connection to the landscape. For Natasha, she felt this connection when hiking up the canyon on their first morning and doing sun salutations on the rim. She was struck by how flat and rolling the landscape was up top and could see the snow-covered Steens Mountains in the distance. For Elisa, it was “sharing the experience [she] had with other people that were so happy to be there, especially Natasha. It was great getting to know a fellow Board member better and spending time in the areas that so many are working so hard to protect.”

For our board members, their time in the Owyhee also strengthened their relationship with desert conservation. “The areas are so vast and damage to them can last so long. One of the camps we stopped in had cow patties everywhere which didn’t seem that new. It made me recognize that cows can damage an area for a long time,” said Elisa.

“This part of the desert is remote and harsh,” says Natasha, “We had so many pounds of gear just to make us comfortable. I am amazed at all the animals and humans that adapted to live in this landscape without these creature comforts. Also, with very few people actually calling this landscape home, it’s easy for its management to be overlooked or coopted. I am happy that groups like ONDA keep watch and take action.“

Conserving the Landscape

The Owyhee’s beauty has been shaped over millions of years. While its remoteness and ruggedness have granted this area a certain level of protection, development pressures have been clawing at its edges. Big, interrelated forces like climate change, fire, and invasive species combined with pressure from mining, natural gas development, a proposed major highway, a new transmission line, and illegal ATV use all pose immediate, serious threats to the wild, intact lands throughout the Owyhee Canyonlands.

ONDA’s community of supporters has worked for decades to conserve the most ecologically important public lands in Oregon’s Owyhee Canyonlands. Our vision is an Owyhee where plant and animal communities flourish, wide-open spaces abound and local communities thrive. Protecting the most special places within the Owyhee Canyonlands would safeguard its rich ancient history, healthy wildlife habitat, fascinating geology and ample recreational opportunities.

We’re thrilled to see exceptional wins for Oregon’s Owyhee Canyonlands since Elisa and Natasha embarked on their trip. We’ve seen land managers prioritizing more acres for conservation and lawmakers push for permanent protections. Most recently, the Bureau of Land Management committed to protecting more than 400,000 Acres in Oregon’s Owyhee Canyonlands, while Senators Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley introduced legislation in the U.S. Senate to permanently protect more than 1 million acres of the Owyhee. We stand ready to push the proposal forward in the weeks and months ahead and look forward to sharing important opportunities to voice your support for this exceptional landscape.