Author: Rachel Renne | Published: February 13, 2023 | Category: Species Spotlight

This article originally appeared in The Source on February 8, 2023.

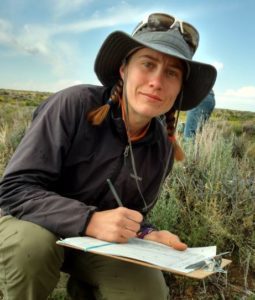

In May 2021, I hiked the entire 750-mile-long Oregon Desert Trail, touring the high desert plant communities of central and eastern Oregon on foot. Throughout this otherwise lonely trek, one plant was my constant companion: the aromatic shrub, big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata Nutt.).

There are 25 species of sagebrush in the western United States, and all but one are in the genus Artemisia (budsage has been renamed from Artemisia spinescens to Picrothamnus desertorum). Although I did occasionally encounter budsage during my walk through Oregon, it was unusual to pass a day without seeing big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata Nutt.). As its common name suggests, this shrub is larger than many of the other species of sagebrush and it gets its scientific name from the three small lobes at the end of each of its wedge-shaped leaves, which resemble a trident. Native to 14 states, big sagebrush is the most widespread of the Artemisia shrubs and has been classified into several different subspecies that each prefer different habitats across the region.

Lower elevation sites with deeper soils support basin big sagebrush — which is easy to recognize by its long, thin leaves and tall, leggy growth form.

Wyoming big sagebrush is round and short-statured and is found at moderate elevations and where soils are shallower. This subspecies can extract water from soils too dry for many other plants — including the other big sagebrush subspecies.

Mountain big sagebrush is found at higher elevations where soils are deeper. This subspecies is often flat-topped but can resemble Wyoming big sagebrush. Connoisseurs can tell the two apart by smell, but even a novice can distinguish them by placing a few leaves in water under blacklight. Mountain big sagebrush leaves glow bright blue, thanks in part to the same chemicals that provide their characteristic sweeter smell.

“Sweeter” is perhaps a relative term. Although big sagebrush is an important food source for animals like the greater sage-grouse, pronghorn and mule deer, it is bitter and unpleasant to humans. Note that we often refer to these shrubs as “sage,” but this is not the sage used in savory dishes. Big sagebrush belongs to the family Asteraceae, along with sunflowers and daisies. Culinary sage is in the Lamiaceae family, with mint, rosemary and thyme as relatives.

Humans are not the only animals in Oregon to find this plant unpleasant to eat. Nearly all big sagebrush ecosystems support livestock grazing, and cattle prefer a diet that excludes this ubiquitous plant. As a consequence, many extraordinary and imaginative methods have been developed to remove sagebrush in an effort to promote grasses and cater to the bovine palate.

Today, big sagebrush is considered a valuable part of the landscape rather than a nuisance — and for good reason. These shrubs engineer their habitat in surprising ways that improve conditions for both animals and plants. Big sagebrush promotes water infiltration and helps maintain snowpack. Its robust root system reaches deep into the soil, allowing it to use water that is inaccessible to most other plants — and then share that water. At night, the big sagebrush’s roots transport water from wetter to drier parts of the soil. This phenomenon, common to many plants, was first discovered in big sagebrush. It’s called “hydraulic lift” because the primary direction of this redistribution is up in these ecosystems where sun and wind rapidly dry shallow soils. In addition to enhancing water resources, big sagebrush also concentrates nutrients in the soils directly beneath its canopy, and these “islands of fertility” can promote recovery after fire.

At first glance, landscapes defined by big sagebrush can appear as monotonous grey-green expanses of shrubs surging towards the horizon. Early descriptions suggested that these ecosystems support low plant diversity, but more recent accounts suggest otherwise. Although it is true that local plant diversity may be relatively low in dry areas, even moderately wet sites often support dozens of species. Even more impressive is the enormous assortment of plants that are found across big sagebrush ecosystems, so that the unique collection of species found at single sites can vary substantially from place to place. Stop and look closer and you will see that big sagebrush canopies can provide favorable microsites for grasses and wildflowers.