In this excerpt from Chapter Seven, “Vapor Trails,” Ellen describes encountering the work of a photographer Terri Warpinski, who had taken to walking out onto the playa at Summer Lake and was slowly drawing a line across the gray, brittle, cracked surface of the dried lakebed with black volcanic rocks, while serving as an artist-in-residence at PLAYA.

When I first noticed it, I assumed it was a fence line. That didn’t make sense. Were those footprints? Eventually we learned it was Terri’s creation. Did the line of rocks go to the far shore? Why was Terri doing it? How did she get the rocks there? These musings in and of themselves expanded our relationship with the playa whether we set foot on it or not. A few residents, giving in to their curiosity, walked the Morse code of it as far as it went then turned around and came back; still others kept going to assess the remaining distance to the far shore, which, mirage-like, always remained a mile or so out of reach.

That’s what I did. I walked past where Terri’s trail of rocks ended. I soon found myself running as though afraid, as though I wanted to get it over with, wanted to get to the other shore and then return to the security of the marked trail that had disappeared from view behind me. The absence of the rocks was somehow unsettling to me. No guide. On my own. Unmarked, uncharted, wild out there in the middle of that vast, inscrutable playa. Life’s trail. Maybe a trail is a way of challenging death. Start at the beginning of something, go to the end—and then, instead of stopping (dying), step off into an undefined else. What are each of us leaving and going toward? Maybe too much of what we do in life is taken up by trying to find the right trail, to resolve ourselves and our lives into a discernable pattern and direction and always in denial about the fact that the trail, as we perceive it, has an end. Even better, make that trail one you don’t have to bushwhack, that is already charted. Most of us are happier with a trail than without one. The reassurance of knowing the remaining distance back to home base, of a known trail, makes us brave-ish. Most of us are happier when someone else is with us on that trail rather than all by ourselves. Most of us are happier with mediated wilderness, guided wilderness, the cruise-shipping of wilderness.

The real McCoy requires that we actually know about survival, finding our way, being without contact, being dirty and uncomfortable for more than a few nights, maybe even lost. Maybe the whole point is to get lost from time to time. Maybe “I found the trail!”—the call you shout back to your hiking companion when you have both lost track—couldn’t possibly feel so good without first getting lost.

Here’s to the Oregon Desert Trail. It gives you ample room and opportunity to feel lost because it doesn’t hold your hand. You map your own way. You swim or sink in the sagebrush ocean. You have the freedom to roam, to call your path your own.

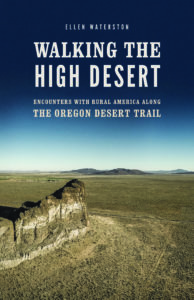

excerpt from Walking the High Desert, Encounters with Rural America Along the Oregon Desert Trail by Ellen Waterston, University of Washington Press, June 2020