The Oregon Desert Trail is an extremely challenging route for hikers, both physically and logistically. ODT travelers need to be aware of the remoteness, lack of cell communication and environmental hazards. There are several potentially dry stretches with no reliable water where water caching ahead of time is necessary. Thru-hiking the entire trail is not for the beginning long-distance hiker. Similarly, those traveling shorter lengths of the trail also need to be fully prepared and aware of the challenges of the ODT.

Challenges and Risks

The Oregon Desert Trail is an unmarked route. Anyone aiming to hike a section or the entire route needs to be prepared to navigate a variety of terrain. We recommend this route for experienced backcountry travelers as over 30 percent of the ODT consists of cross-country travel. Know how to use your map and compass, and practice, practice, practice. The ODT resources (maps, guidebook, data book/water chart, recreation maps, compass, GPS, water cache guidelines, common sense) are all designed to be used together to successfully navigate the route.

Those wishing to develop their skills for a challenge like the ODT can look for map and compass workshops at your local REI or outdoor store, or try out an online navigation class.

ALWAYS carry paper maps, even if primarily using a GPS for navigation. Technology can fail, devices can break. Take a map and know how to use it.

GPS enabled smart phone apps have come a long way, and they are another tool hikers can use to navigate the unmarked route. There are plenty GPS enabled apps that will work on most smart phones, even while in airplane mode. Gaia GPS has been used by multiple ODT hikers with success; be sure to download your maps for off-line use.

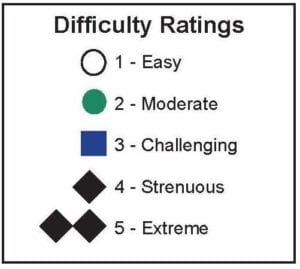

We have tried to qualify each section of the ODT with a skills rating, but in the case of any subjective information, use these ratings as a basic guideline. Many people have different skill levels and experience, and different ideas of what a “Challenging” section means versus a “Strenuous” section.

For those new to hiking a route versus a trail, consider starting with an Easy or Level 1 rated section. Refer to the skills progression for ideas about how you can develop the advanced skills needed to successfully hike a challenging route like the ODT.

Time of year plays a big role in the difficulty levels; for this skill level rating, conditions will be assumed to be in spring or fall when temperatures are more conducive to hiking a desert route. Please use all the ODT resources together to hike as they all play an important roll in guiding you in having a safe and successful hike.

Because the difficulties of the route can come from different factors, each section will have a rating from 1-5 for Terrain, Navigation and Water Availability.

Terrain: miles of trail, cross country, primitive road, maintained road and paved road.

Navigation: marked trail, unmarked trail, cross country, many changes in direction (NOTE: there are no ODT trail signs anywhere on the route).

Water Availability: brief overview of reliable, questionable and unreliable sources in each section (please refer to our databook/water chart for detailed water information)

These ratings were developed within the context of the entire ODT; an easy

rating for the ODT would not be comparable to an easy rating on other trail

systems, just in relation to the other ODT sections

Skills Progression

Here are some ideas about how you can develop the skills needed to successfully hike an unmarked route like the ODT.

Take a navigation class: Your options include watching online tutorial videos, taking a class at your local outdoor store or signing up for a guided field trip.

Practice on trails: Carry a map on hikes that are on trails, and frequently check the map to get a feel for how topo lines translate into features around you.

Practice NEAR trails or very visible landmarks: Go off-trail between two easy-to-find ‘handrails’ like a river and a road, or between two established trails. If you get off course you can always travel towards the handrail.

Practice micro-navigation: The art of making small route choices on the ground, or “micro-navigation” is just as important as the skills you learn in navigation classes.

Practice in an urban setting: Try putting together a complicated walking route with lots of turns, go for a trip and practice with a paper map. If you’re really lost, you can always check your phone or find a ride home.

Anticipate the terrain: Beyond knowing where you should be on the map now, look ahead and predict what you will do next. Study your maps right before your hike to get a lay of the land, and repeat at each break.

Go with more experienced people: Hike with an experienced navigator, and watch what they do and follow along.

Learn on maps before GPS: GPS devices and smart phones have become incredibly common and utilitarian, especially when hiking off-trail. However, it’s still important to have the analog skills of map reading and navigating.

Review the route before your hike: Review your proposed route several times, identifying notable landmarks, challenging stretches, potential camping areas and possible exit routes in case of an emergency.

Build skill development into your objective: Try adding a skill that you can improve on into the core goal for each trip you take. This helps create a challenge that will keep you interested and inspired.

Be willing to adapt: Mother Nature doesn’t have a copy of your itinerary. The keys to hiking a route are preparation, adaptability and objectivity. If you aren’t sure that a particular area will be navigable, have a Plan B.

Make good decisions: Listen to your body, observe the terrain and weather, carry the resources you need to make route decisions in thefield and remember to enjoy yourself! Taking a rest day, or a side trip for ice cream are good decisions if they keep your morale high and your feet happy.

Creeks, canals, springs, water troughs, water holes … the ODT depends on a variety of water sources. Water sources are indicated on maps with color-coding to match the data book/water chart and the reliability of the source.

Many wells and water facilities (cow tanks/troughs) on public land are maintained by private landowners; please respect all wells and facilities you may find along the trail. Use the data book/water chart to plan your water strategy; even sources listed as reliable are subject to the whims of nature since water in the desert is never a guarantee. Instead, these ratings should be weighed with your own judgment of conditions in a given year or season.

Many experienced desert hikers believe any water in the desert is good water, and expecting a wide range of sources is important.

The water sources in the data book/water chart are based on field observations of availability, but conditions may change every year. Your help in collecting data on water sources will help future hikers. Please see the data book/water chart for more information on collecting data. A “reliable” water source on the ODT is one that, based on field observations and assessment of the source, is sufficient for obtaining water. A “questionable” water source is one that had inconsistent available water during inventory. An “unreliable” water source was of either low quality or dry during inventory.

Naturally occurring water sources and water sources developed for use by livestock are not tested and may contain harmful pathogens, diseases, or chemicals. If you chose to drink from an untested water source the water should be boiled, passed through a water filtration system, or chemically treated as a minimum precaution.

Caching of supplies, including water containers, is prohibited within national wildlife refuges and national forests, please refer to our cache guidelines about proper caching technique, and plan accordingly.

Spring

(April to June)

Pros: mild to hot daytime temperatures, increased water availability, longer days.

Cons: weather inconsistent, snow may be present at highest elevations, mosquitoes in some marshy area, ticks more abundant.

Summer

(July to August)

Pros: mild to hot daytime temperatures at highest elevations.

Cons: scorching temperatures at lower elevations, decreased water availability, high fire danger.

Fall

(September to October)

Pros: mild to hot daytime temperatures, no mosquitoes.

Cons: weather inconsistent, decreased water availability, high fire danger, shorter days, cold nights, hunting season requires extra care.

Winter

(November to March)

Pros: mild/cold daytime temperatures in lowest elevations.

Cons: cold to freezing days/nights, heavy snow in higher elevations, weather inconsistent, decreased/frozen water availability.

Many access points for the Oregon Desert Trail are not suitable for regular passenger cars. In addition to being a high-clearance, 4wd vehicle, vehicles traveling in Oregon’s high desert should have the following:

At least one full-size spare tire, with car jack, lug wrench, and a 1’x1’ square of plywood (or similar—something to set the jack base on in sandy soils). Practice putting on the spare tire in a nonemergency setting is very important!

Extra key in a magnetic hide-a-key box. It’s no fun driving with a broken window because you had to break into your car to get your locked-in key.

Extra fuel for the vehicle, extra engine coolant and extra engine oil.

At least one gallon of extra drinking water.

Jumper cables, Fix-A-Flat, tow-strap, and a flashlight. Consider a small DC-powered air compressor.

After a significant rain event, desert soils/primitive roads may become too supersaturated to drive on, especially in the Owyhee and Alvord Desert region.

Shovel and possibly a fire extinguisher. Check with local BLM, Forest Service, and National Wildlife Refuge offices for fire danger levels and whether these items are required.

Note that roads with vegetation may be closed during times of extreme fire danger due to the flammable nature of dried grasses.

Camping along the ODT can often be a challenge. In some areas flat ground may be in excess, but clear open ground may not. Be prepared for limited spaces for setting up a tent, and sandy soils that thwart your tent stakes.

Many sections along the Oregon Desert Trail do not have trees, and strong winds may make camping a challenge. Choosing to “cowboy” camp, use a free-standing tent, or use a bivy sack leaves the ODT hiker with more options for a night’s rest.

If backcountry camping within the Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge boundaries you will need a permit to spend the night outside the established campgrounds. There is no backcountry camping allowed at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge.

On warmer summer days the western rattlesnake can be found sunning on rocky outcroppings. Take care when walking through tall grasses; wearing tall gaiters and beating the brush with a hiking stick can prevent unwanted close encounters with these desert creatures. Rattlesnakes do not always release venom during a defense bite, however, it is best to assume venom has been delivered and act with all haste and seek medical treatment. Read more here about treating rattlesnake bites.

On warmer summer days the western rattlesnake can be found sunning on rocky outcroppings. Take care when walking through tall grasses; wearing tall gaiters and beating the brush with a hiking stick can prevent unwanted close encounters with these desert creatures. Rattlesnakes do not always release venom during a defense bite, however, it is best to assume venom has been delivered and act with all haste and seek medical treatment. Read more here about treating rattlesnake bites.

Ticks can be prevalent in eastern Oregon, especially in the spring. Wearing long pants and socks can help prevent tick bites, especially when walking through tall grasses in cross country sections of the route. Read more here about tick removal guidelines.