Author: Gena Goodman-Campbell | Published: March 19, 2025 | Category: Notes from the Desert

Illustrating the restoration process at Robinson Creek

Over the past two decades, Oregon Natural Desert Association has partnered with the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs on a variety of restoration projects for the benefit of fish, wildlife and cultural uses. Each project seeks to restore natural processes and improve habitats on Tribally-owned lands.

Because ecological restoration often unfolds over many years, with changes that take place incrementally over time, it can be difficult to envision the ways that a stream will transform in response to our actions. So when we recently set out to create an ambitious watershed restoration plan for Robinson Creek—a tributary of the John Day River that flows through a conservation property owned by the Tribes—we wanted to find a way to help people visualize the change we aim to create in the ecosystem through our restoration actions.

Illustrating the Restoration Process

As we researched how other restoration plans have done this effectively, we kept coming across illustrations by Maisie Richards of Round Water Design. Maisie is a trained fluvial geomorphologist—a scientist who studies how rivers form and change the landscape—who is also a talented artist. She specializes in illustrating the natural processes she studies.

When Jefferson Jacobs, ONDA’s riparian restoration manager, and I first met with Maisie, the strong connection between her work and ONDA’s was immediately clear, and we agreed to hire her to create an illustration for the Robinson Creek Restoration Plan. Through a series of conversations, and the live, graphic note-taking technique known as scribing, Jefferson and Maisie collaborated on a visual representation of ONDA’s riparian restoration process. What began as one illustration grew into a series of four illustrations that conceptualize the natural processes ONDA encourages with our restoration efforts. Jefferson and Maisie recently presented these illustrations at the River Restoration Northwest symposium, where they were received with great enthusiasm by both restoration practitioners and tribal leaders.

Holistic Approach to Restoration

While these illustrations were created for the Robinson Creek Restoration Plan, they epitomize ONDA’s riparian restoration methodology and the process we undertake on our stream restoration projects across Oregon’s high desert.

ONDA’s approach to restoration is one of observing the ecosystem and the way it responds to our actions, then taking deliberate steps to put the stream on a trajectory of self-sustaining recovery and resilience. When we first undertake a project, we seek to understand the root causes that are preventing a stream from functioning at its full potential. Across Oregon’s high desert, these issues are often rooted in more than a century of misuse, which has resulted in ecosystems that are out of balance. When this is the case, the environment is unable to adapt to drought and climate change and conditions worsen.

Creating a Plan for a More Resilient Future

The story of Robinson Creek is one that mirrors that of many streams in Oregon’s high desert. Where there once was a thriving riparian forest carpeting the entire valley floor, more than a century of intensive livestock grazing left the stream with very little streamside vegetation. Concurrently, trappers removed nearly all of the beaver from the watershed. Without beaver dams to hold back water, erosion accelerated to the point where Robinson Creek now flows through a deeply cut channel, disconnected from its historic floodplain. Thirsty juniper trees, which were not historically found along streams, moved into the floodplain to take the place of beneficial trees like willow, aspen and cottonwood, further reducing the water flowing into the creek.

Once this landscape was secured for conservation management, ONDA and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs partnered to add streamside plants along Robinson Creek in the limited locations where there was enough water for them to survive. However, we soon recognized that a more comprehensive approach was needed to achieve our vision of a flourishing ecosystem. Beginning in 2023, ONDA worked with the Tribes to develop the Robinson Creek Restoration Plan, which was completed at the end of 2024. Now, we are preparing to launch an ambitious 5-year effort that will restore four miles of Robinson Creek.

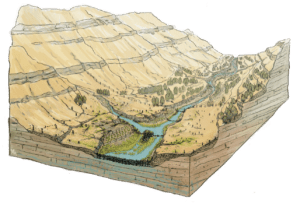

Before Restoration: A System out of Balance

Much of our plans for the Robinson Creek restoration project focus on influencing what is happening underground, in the hidden yet essential world beneath the stream called the “hyporheic zone.” When water from the stream infiltrates through porous sand and gravel in the stream bed and banks, it flows below and around the stream where it is cooled, lowering the temperature of the entire stream once this water is slowly released back into aboveground flows. Water flowing through this underground stream also irrigates surrounding plants, creating a balanced cycle that is emblematic of a healthy stream system.

But when a stream channel has been eroded down below its floodplain, water doesn’t reach as much of this underground area and native plants die off due to lack of water. With no beaver dams or woody debris in the stream to slow it down, water flows through quickly, taking all of the valuable sediment and nutrients with it. Once a stream like Robinson Creek is in this state, it can become stuck in a detrimental cycle of erosion and drying.

Years 1-3: Restoration Begins

With beaver currently absent from the Robinson Creek watershed, human intervention is critical to jumpstart the recovery of natural processes. ONDA and our volunteers will temporarily step into the role of ecosystem engineers, taking actions to reconnect the stream with its floodplain, capture sediment, and restore a thriving riparian forest.

We will start by installing a system of monitoring wells to track what is going on in the water table and to learn how this underground world responds to our restoration actions. Then, we will channel our inner beavers, building hundreds of instream structures that mimic beaver dams and the natural accumulation of logs and debris found in a healthy stream. By adding structure and complexity back into the creek, we will slow water down and capture sediment. This will raise the water table so that it can fill the underground hyporheic zone and stay on the landscape longer, resulting in cooler and more consistent stream flows year-round.

Additionally, we will remove western juniper to increase the amount of water flowing into the stream, especially near valley bottoms where their impact is most significant. Finally, we will begin strategic planting efforts, with careful consideration given to selecting locations where the water table has risen enough to ensure trees and shrubs like cottonwood and willow can survive. Temporary fences will be installed to protect new plantings from hungry beavers and other wildlife until plants are mature enough to survive “browse,” or being eaten by animals.

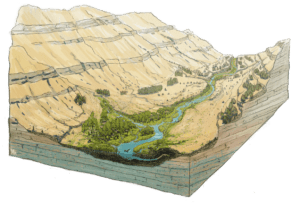

Years 3-5: Restoration Starts to Create Positive Changes

A few years into the restoration project, the ecosystem will have begun to respond positively to our restoration actions. We will continue to establish additional planting areas, which will start small to focus on creating deep, resilient root systems. As the water table rises and expands the areas where plants can survive, we will begin planting densely in larger areas to restore the thriving riparian forest that will be needed to support a self-sustaining ecosystem. Protective fences will be maintained until the youngest plants are well-established, typically at five years old, after which they will be removed all at once.

At this point, it’s possible that a beaver family could naturally move in and begin constructing their own dams, creating ponds that raise water levels, providing denning sites that protect young beavers, while also supporting the positive ecological changes driven by restoration actions. These changes will have improved the hydrology of the creek, with slower water flow leading to a recharged water table. Although some natural regrowth of shrubs like willow may have begun, it will not yet be enough to sustain the beaver family through the winter, necessitating the additional food sources that will come from our restoration plantings once they mature.

Year 5 & Beyond: Self-sustaining Recovery

After five years, the trees and shrubs we have planted will be strong enough to support wildlife browse, and temporary fences can be removed, allowing plantings to thrive and expand. The vegetation will also have matured enough to significantly improve stream conditions and provide a new resident beaver family with adequate food and building materials. The system has become self-sustaining and resilient, with ongoing dynamic changes that continue to build upon earlier restoration efforts.

While the restoration project is officially complete, the overall restoration trajectory is recognized as a dynamic, evolving process, where continuous improvements and adjustments will further shape the stream towards a healthier and more resilient state over time. Through this adaptive approach, ONDA remains flexible and responsive to the evolving conditions of the ecosystem.